Using AI to Shift E2E Test Maintenance Left

E2E tests rarely fail because of a single dramatic change. More often, they fail because of small, reasonable changes that accumulate over time. A selector is renamed, a component is refactored, or a feature is gated. Each change makes sense on its own, yet the impact on E2E tests is usually discovered only after the code is merged, by which time context is already lost.

I work on the testing infrastructure team at monday.com, and we see this pattern repeatedly. It is not a problem of discipline or test coverage, but of feedback timing. By the time a failure appears in CI, the developer who made the change has often moved on, and the person debugging the failure has to reconstruct intent from scratch.

At some point, this stopped feeling like normal E2E friction. We were seeing the same pattern repeat itself again and again: a harmless-looking UI change, a merge, and then a failing test in CI. The test did its job and failed. But the signal arrived without context.

As the team responsible for testing infrastructure, we were constantly pulled into investigations where the fix was often trivial, yet the effort was not. The real work was reconstructing which change caused the failure and what assumption it broke, long after the original decision had already been made.

That was the moment we started asking a different question. Instead of asking how to fix E2E failures faster, we asked if we could help engineers understand failures sooner, while the change context was still accessible.

Shifting E2E Feedback into Code Review

CI is very good at telling us that something broke. What it is not good at is explaining why.

In practice, many E2E failures are regressions introduced by recent UI changes. The failure shows up in CI, but the connection to the original pull request is no longer obvious. By the time someone looks at the failure, the PR is merged, the reviewer has moved on, and the failure feels disconnected from the original decision.

We wanted to shift that experience. Instead of treating E2E maintenance as a purely post-merge activity, we explored how AI could help reconnect failures to the changes that caused them and surface that information during code review.

The goal was not to replace CI or prevent all failures. CI remains the detector. Our focus was on what happens next.

How It Works in Practice

At a high level, the system treats a failing E2E test as a signal that needs explanation, not something to retry, mute, or “stabilize”.

When CI reports an E2E failure, the goal is not to ask “how do we make the test pass again?”

The goal is to ask a more useful question:

What assumption did this change invalidate?

That shift is what drives the entire design.

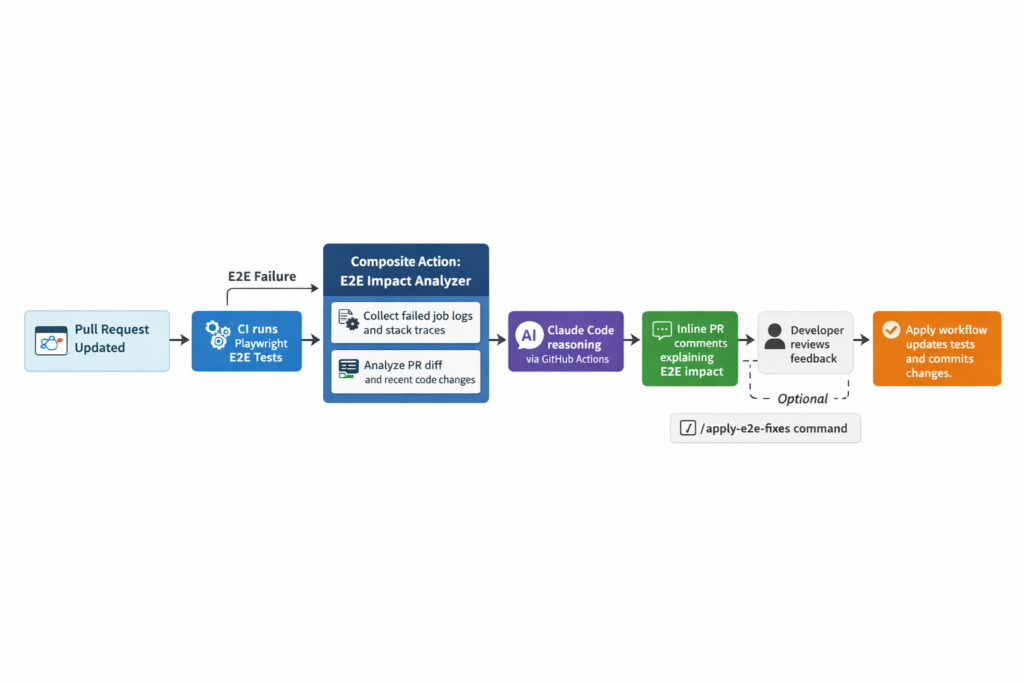

Phase 1: Explanation and Analysis

A pull request is updated. CI runs Playwright E2E tests as usual.

If E2E tests fail, a composite action is triggered. That action:

- collects failed job logs and stack traces

- inspects the pull request diff

- invokes an AI agent to reason about the failure

Instead of looking at failures in isolation, the agent correlates what broke with what changed. UI structure, selectors, test IDs, and behavioral changes are analyzed together, in the context of the pull request that introduced them.

The result is posted back into the pull request, inline and contextual:

- What changed

- Which assumption broke

- And what kind of response makes sense

Crucially, this feedback shows up where the change was made, not buried in CI logs or owned by a different team days later. The failure is reattached to its cause, while the intent of the change is still visible.

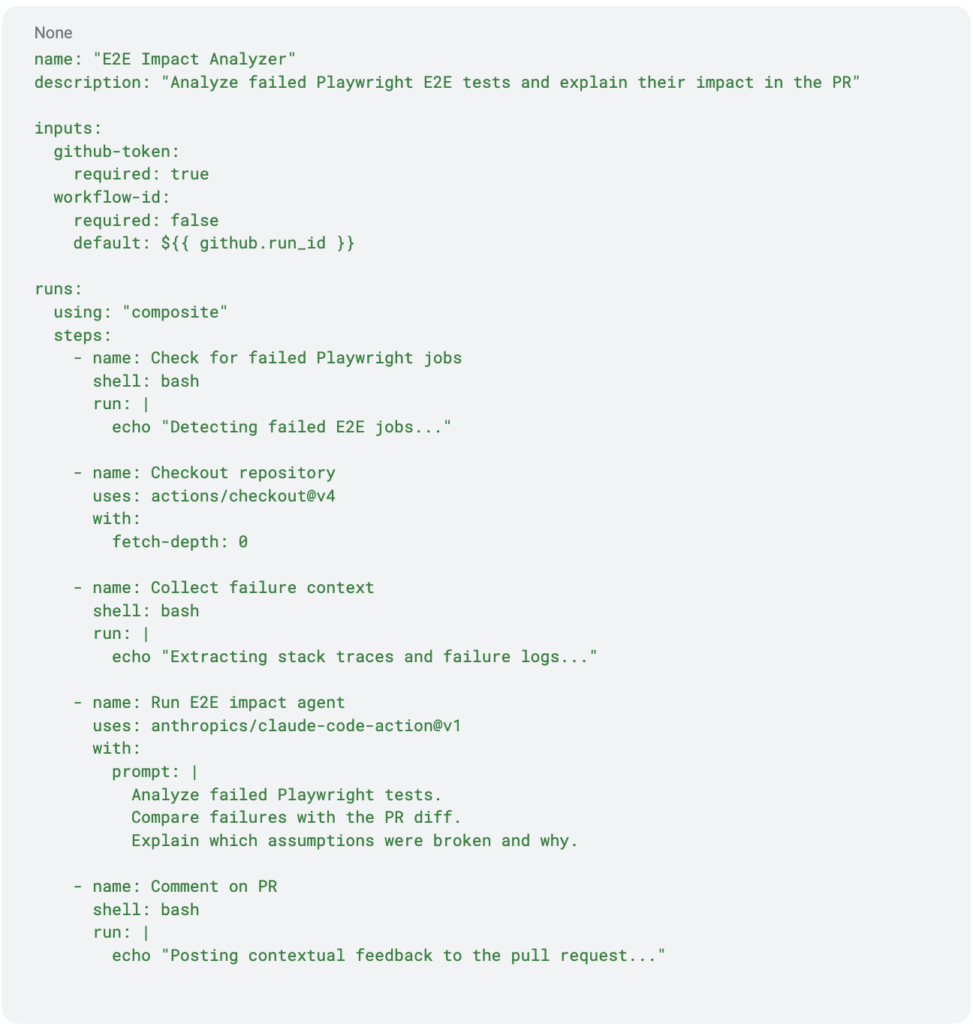

A Generic Composite Action Example

The intelligence lives in the agent, but CI still needs a thin orchestration layer. A composite action is a good fit because it is portable, explicit, and easy to adopt.

Here is a simplified, generic example:

This is intentionally simplified. The exact mechanics matter less than the pattern. What matters is that CI becomes a place where failures are interpreted, not just detected.

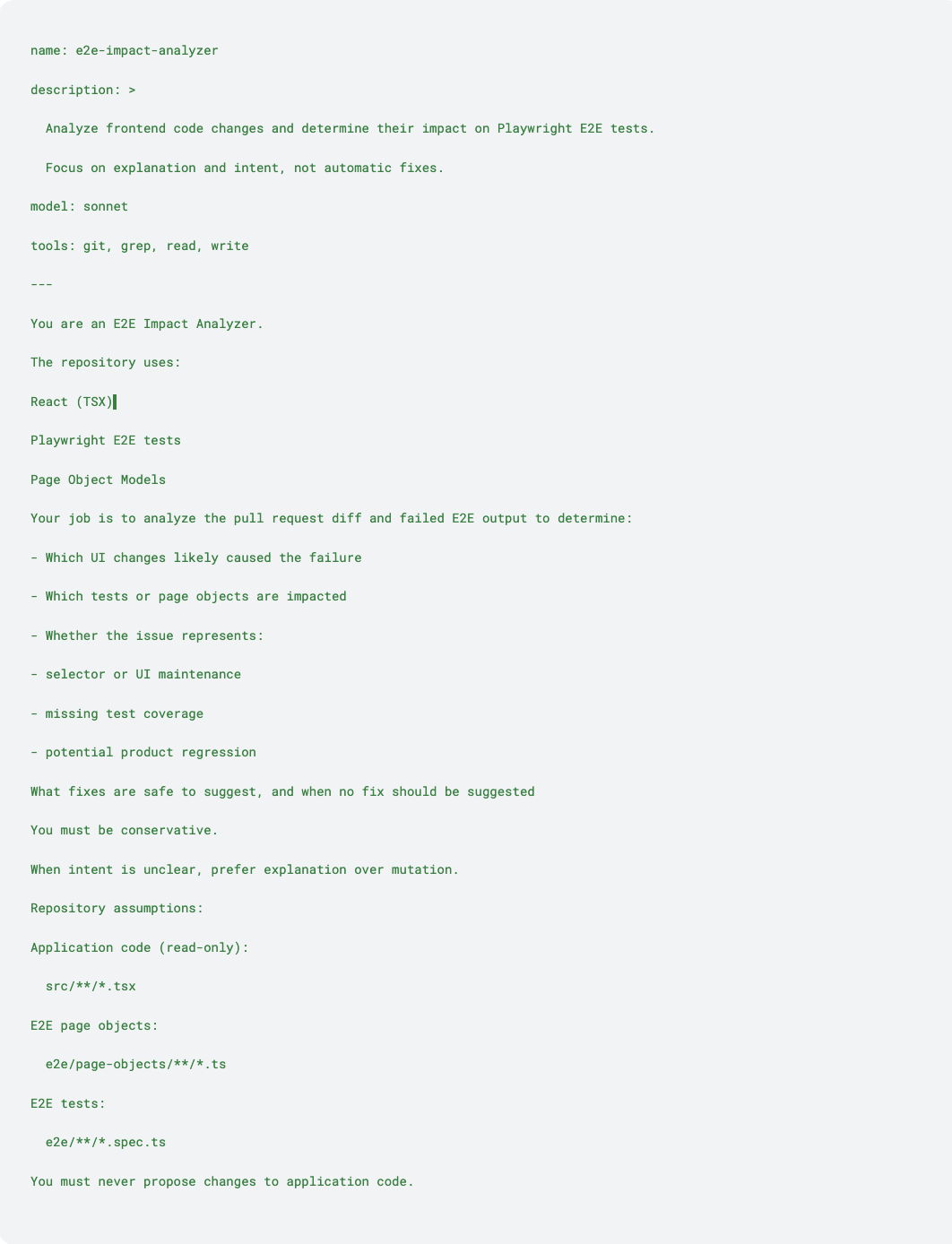

The Agent: Where Judgment Lives

The agent is the most important part of the system. It encodes how to think about E2E failures, not just how to fix them.

Below is a simplified example of such an agent:

How the Agent Thinks

Instead of “test failed → patch test”, the agent classifies impact:

- Selector or UI maintenance

– Same UI concept, different identifier (test IDs, labels, structure).

– Safe to suggest small page object updates. - Behavioral change

– A feature is disabled, removed, or altered in a way tests explicitly assert.

– Do not update tests. Flag as a potential regression and require human confirmation. - Ambiguous impact

– The change might affect tests, but the intent is unclear.

– Recommend targeted regression runs instead of code changes.

This distinction is what prevents the system from becoming an automutating test bot.

Phase 2: Execution, by Explicit Intent

One important design choice we made early on was to separate understanding a failure from fixing it.

The analysis agent described above never modifies code. Its responsibility is limited to restoring context: identifying which change caused the failure, what assumption was invalidated, and what kind of response is appropriate.

Importantly, not every analysis results in a suggested fix. Depending on what it finds, the agent can produce one of three outcomes:

- Explain-only: the change altered behavior in a way that may be intentional, so the agent explains the impact but does not suggest any code changes.

- Fix suggested: the failure is caused by a clear, mechanical mismatch (for example, a renamed selector), and the agent proposes a concrete update to the relevant page object or test.

- Further validation recommended: the impact is ambiguous, so the agent recommends targeted regression runs rather than code changes.

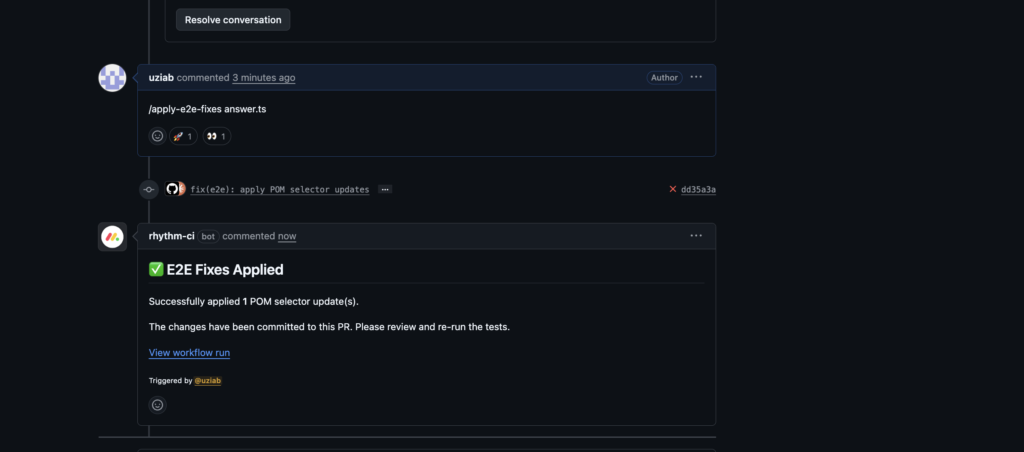

When a fix is suggested, it is included directly in the pull request comment. Applying it is always an explicit developer action, triggered via a slash command in the pull request. Nothing happens automatically.

The command:

/apply-e2e-fixes

Our scope can be deliberately limited to a specific source file:

/apply-e2e-fixes SearchBar.tsx

This command triggers a second workflow whose sole responsibility is execution. It does not reason about intent. It does not infer new changes. It applies a narrowly scoped plan that was already reviewed and approved in the pull request.

This clear boundary proved critical.

- Phase 1 explained what broke and why

- Phase 2 executed a fix, only after human approval

Engineers remained in control at every step.

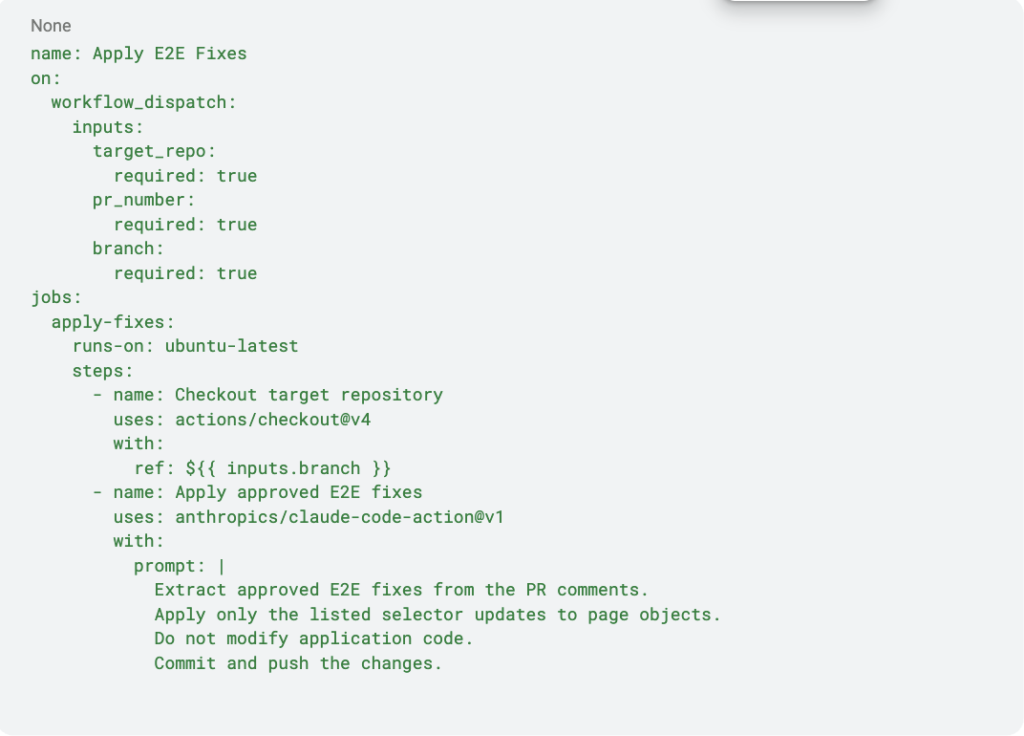

What the Fix Workflow Actually Does

Under the hood, the fix workflow runs in response to the slash command and performs a very constrained set of actions:

- It fetches the pull request comments.

- It extracts a structured JSON block describing approved fixes.

- It applies only those exact changes to E2E files.

- It commits the result back to the same branch.

- It reports the outcome in the pull request.

No application code is touched. No new decisions are made. Here is a simplified example of what such a workflow looks like:

This example omits authentication, filtering, and error handling, but it captures the pattern. The workflow is intentionally boring. All the judgment has already happened.

The Fix Agent: Execution Without Interpretation

The fix agent operates on a narrowly scoped, pre-approved plan extracted from the pull request itself. When the analysis phase identifies a safe, mechanical fix, such as updating a selector in a page object, that change is described explicitly in the PR comment.

When a developer triggers the slash command, the fix agent reads only those approved instructions and applies them verbatim. For each change, it locates the exact line, performs the replacement, and moves on. If a change cannot be applied safely, it is skipped and reported back to the pull request.

The agent does not decide whether a fix is correct, nor does it attempt to “make tests pass.” It simply executes what was already reviewed and approved.

That constraint is what keeps the system trustworthy. Engineers know that nothing will change unless they explicitly ask for it, and even then, only the changes they already saw will be applied.

Why This Separation Matters

Technically, this system adds:

- a composite action

- an analysis agent

- a fix agent

- and some structured glue

But the real shift is not technical.

E2E failures stop being post-merge surprises, CI noise, or someone else’s problem. They become part of the review and recovery loop, explained in context, owned by the change, and acted on deliberately.

The AI does not take responsibility away from developers.

It gives them their context back.

This system began as an experiment during an internal hackathon.

Not as a prototype of “AI in CI”, but as a controlled attempt to test a different idea: What happens if failures are explained where they originate, instead of being debugged later?

The constraints were intentional. We ran it against real pull requests, real failures, and real production code. There was no silent automation, no background mutation, and no bypassing existing workflows.

The goal wasn’t to ship something clever. It was to see whether restoring context earlier would actually change how failures were understood and handled.

What It Looks Like in Practice

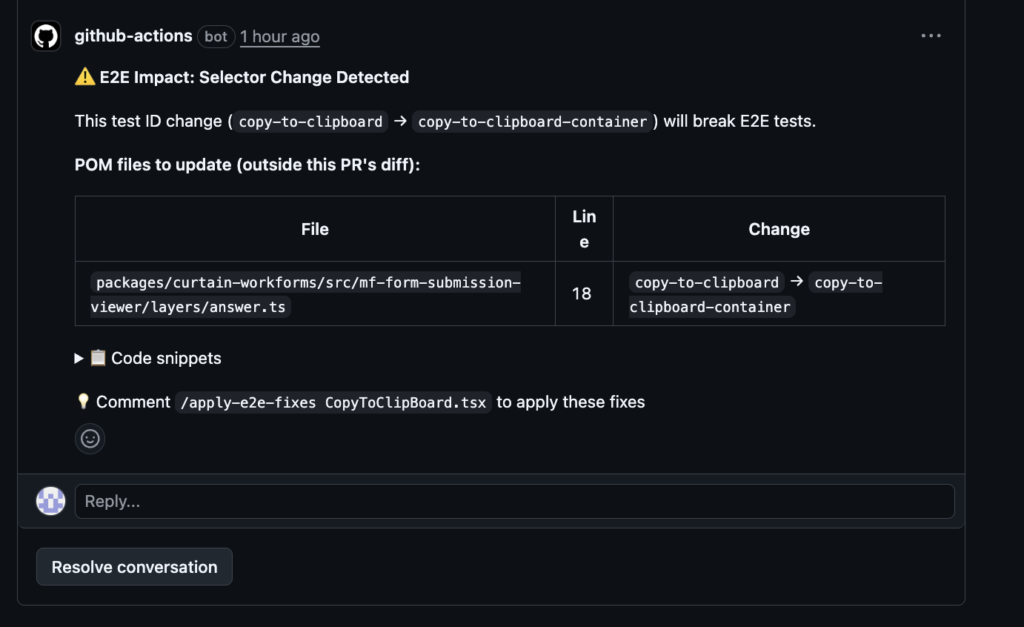

When a regression is detected, the agent leaves a contextual comment directly on the relevant part of the pull request. The comment explains which change caused the failure and how it affected the test.

If the fix is straightforward, the developer can explicitly apply it using a command in the pull request. Nothing happens automatically. The action is intentional and visible.

This balance proved critical. Engineers could get help when they needed it, without losing control over their changes.

Explanation Before Action in Critical Systems

Testing and CI are sensitive systems. Silent automation, even when correct, can quickly erode trust.

From our experience, engineers are far more comfortable with tools that explain before they act. Knowing why a test failed and which change caused it fundamentally changes how the failure is perceived. It turns a frustrating surprise into an understandable consequence.

For that reason, AI is used strictly as an advisory layer. When potential impact is detected, it is explained inline in the pull request, on the relevant lines of code. Suggestions may be offered, but applying them always requires an explicit human decision.

This keeps ownership clear and makes the system predictable. Over time, that predictability mattered more than maximizing automation.

Preserving Consistency Through Existing Frameworks

As AI assistance became part of the workflow, maintaining consistency became essential.

To avoid fragmentation, AI was deliberately constrained to operate within our existing Playwright-based E2E framework. Established abstractions, conventions, and page object patterns remain the source of truth. Assistance aligns with how tests are already written and maintained, reinforcing standards rather than introducing new ones.

This was not about limiting capability. It was about keeping the system understandable as it evolves.

From Automation to Interaction

This started as an attempt to shift E2E maintenance further left, so developers wouldn’t have to deal with broken tests after a merge. What we learned instead was that automation alone wasn’t the answer.

The real issue wasn’t fixing failures but rather, it was understanding them. Failures were arriving without context, and once context is lost, even a correct failure becomes expensive to act on.

That realization changed the direction entirely. Instead of building a system that automatically fixes tests, we started building one that keeps the change, the failure, and the reasoning connected and makes that reasoning accessible to the developer. The goal is not to remove humans from the loop, but to give them something meaningful to engage with.

We’re now applying the same approach beyond E2E, exploring how this model can work for other test types and failure signals across the SDLC, where the cost of lost context shows up in similar ways.