How we detect abusive content in monday.com campaigns

monday.com Campaigns is a recent addition to the monday.com family of products. It helps marketers create and manage the lifecycle of marketing campaigns across different channels, creating audience segments to control who the campaign reaches, and is deeply integrated into monday.com’s ecosystem.

Marketing campaigns are external-facing, as they involve sending various types of content from monday.com to end users. As a result, there is always a risk that the features could be misused. This could lead to potential harm for monday.com in the form of reputational damage, legal liability, and impacted deliverability. At the same time, end users could be negatively affected if they become targets of phishing or scam campaigns.

“With great power comes great responsibility,” a wise uncle used to say, so how do we prevent malicious users from having their way? We have started by outlining this as a classification problem: we want to know whether a campaign is abusive or not, and if it is, prevent it from being sent.

If you’re at all familiar with Machine Learning, you’ll have encountered at least once the classic ever-present example of how to use Naive Bayes to make an email spam classifier. That’s what popped up in my mind immediately as we started discussing internally how to handle this project, with some good – and some bad – memories from my time in university. Ah, nostalgia! But I digress; let’s first go into how we defined the task and how that informed the approach we took.

So first of all, what does it mean to be abusive?

I had a vague understanding of it at the beginning, but thanks to our legal team, the picture became clearer. I will not bore you with the whole definition. Still, essentially, there are different situations that may be considered terms-of-service infringement. These range from fraudulent content, such as impersonating a brand for a phishing campaign, to hate speech or promoting violence in the content of the campaign. Some of these categories lack clear definitions, and some are more important than others.

The outcome of this step was an extensive definition of the different categories of abuse, ranked by importance, their potential content, and the methods for evaluating each. This outlines our multi-label classification task.

I mentioned that we wanted to check before sending whether a campaign is abusive. Since we’re talking about classification, we knew it was going to be hard to catch every abusive campaign. Something was always going to slip by.

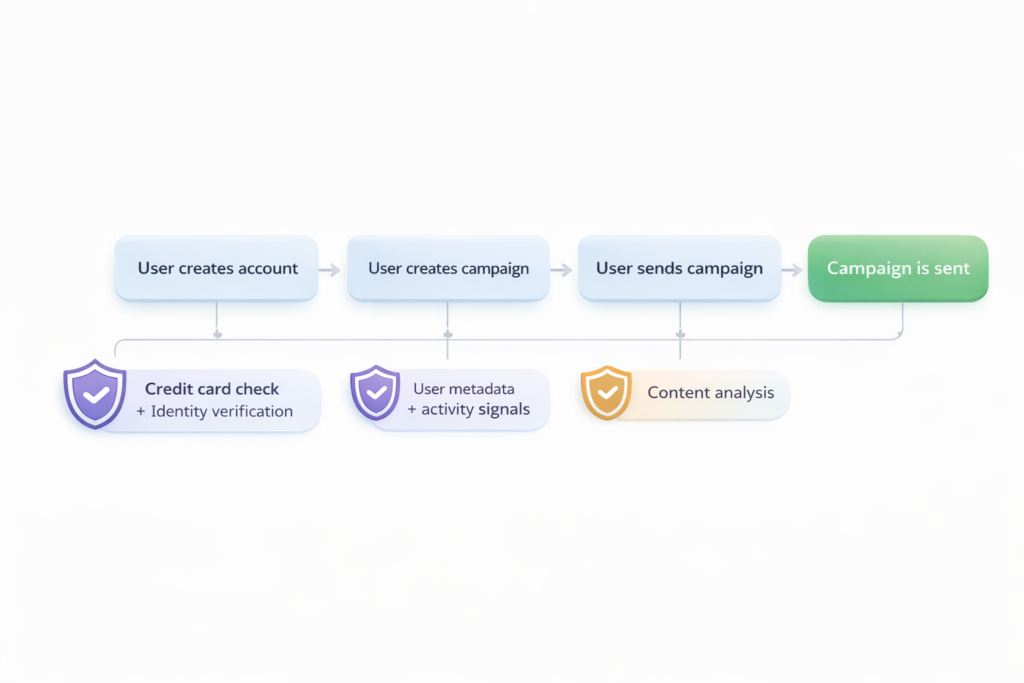

A good way to minimize this probability is to use defense-in-depth. As the product’s feature set grows, so do the potential attack vectors a malicious user could leverage to run an abusive campaign.

We wanted a flexible system that we could easily extend to cover all these attack points in the malicious user journey to steal credit card information, and that, somewhat like a funnel, would minimize the probability of success by introducing multiple obstacles along the way. Data and signals could be gathered from user activity on the platform and used at different stages to classify whether the campaign to be sent was abusive and whether the user was malicious.

This foundation provided us with a rigorous understanding of the problem space necessary to navigate Machine Learning solutions. It also made for a good list of the functional requirements and behaviors that we now use to guide the design and engineering work required to build the whole system.

Our first iteration consisted only of the content analysis bit in the diagram below, but I’m foreshadowing a little of what’s to come later…

Simplified user journey and possible attack surfaces

Naive-first solution: LLMs and content analysis-only defense

Like the good engineers we are, we first looked if there was anything out there we could use, a tool or a third-party service, but the results were not that promising. This was a domain-specific classification problem where data and model requirements evolve with the product. Competitors also leverage internal tools, so we decided to build our own.

Today, the most cost-effective and straightforward way to do classification is with LLMs. We decided for the first version to leverage this as the sole, simplest, and fastest way to get a classification component up and running. No heuristics, no ensemble, single step.

It’s very hard to compete with the scale of data these models are trained on outside specific domains or tasks, and they also make it quite simple to generate synthetic data to jumpstart the task. This eases much of the lifting you’d traditionally have to do with modeling and data gathering. Still, regardless of the approach, the most important elements remain evaluation, formulating a baseline, and understanding the system’s trade-offs.

I’ll spend some additional words on evaluation, which has the most critical role in the system. In an abuse detection system, the classification outcome has real consequences, especially at scale: missed abuse harms users, the platform loses trust, and regulatory issues can increase costs.

The main tension here is between catching all possible abuse (recall) and not annoying users by falsely flagging their campaigns (precision). Clearly, the outcome imbalance between these two situations means we want to prioritize the former, recall, rather than the latter. These are the main components:

- Test dataset: given our definition of abuse, some example open source email datasets, we generated a synthetic multi-label dataset. This ensures good representation of the classes and taking care to include also some common attack patterns and challenging edge cases (eg, for phishing, encoded XSS scripts)

- Metrics: we leverage a multi-layer approach,

- Rule-based: we compare predictions to ground truths, compute a multi-class confusion matrix, and report metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1.

- LLM-as-a-judge: Unlike the classical metrics above, this helps us evaluate hard-to-quantify metrics, consistency, violation reasoning, and the logical alignment of scores, providing additional metrics with stronger semantic validation.

The evaluation allowed us to systematically approach prompt optimization: we tried 0-shot to few-shot prompting, explicit guidance per category. Of course, there are many tools that allow you to automate prompt optimization (eg DSPy), but we decided that it was better to start with a manual approach. Eventually, we arrived at the initial prompt that maximized recall across all categories. Additionally, it became the cornerstone of how we iterate on classification as we get more data from real campaigns and can assess weaknesses in the system.

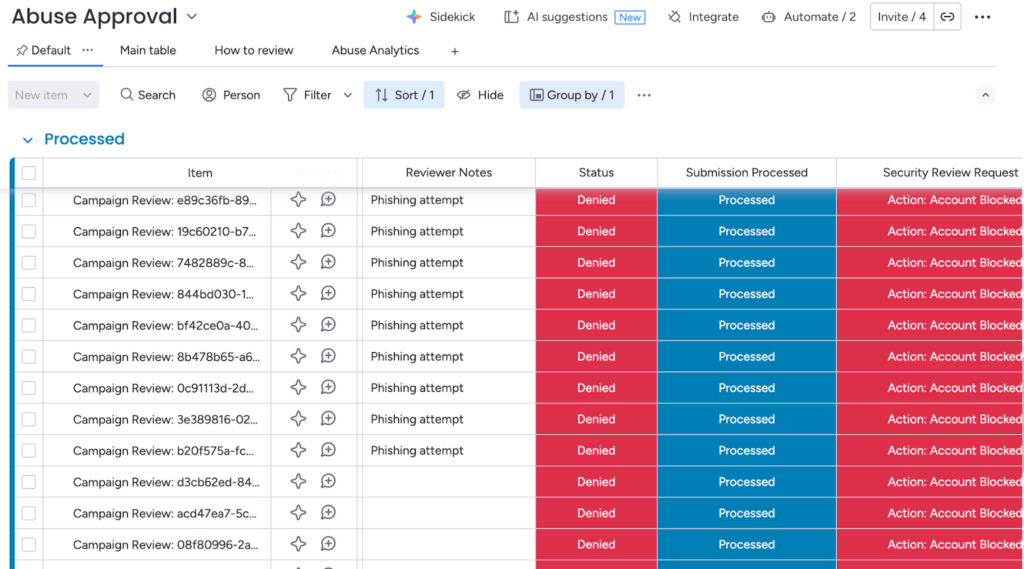

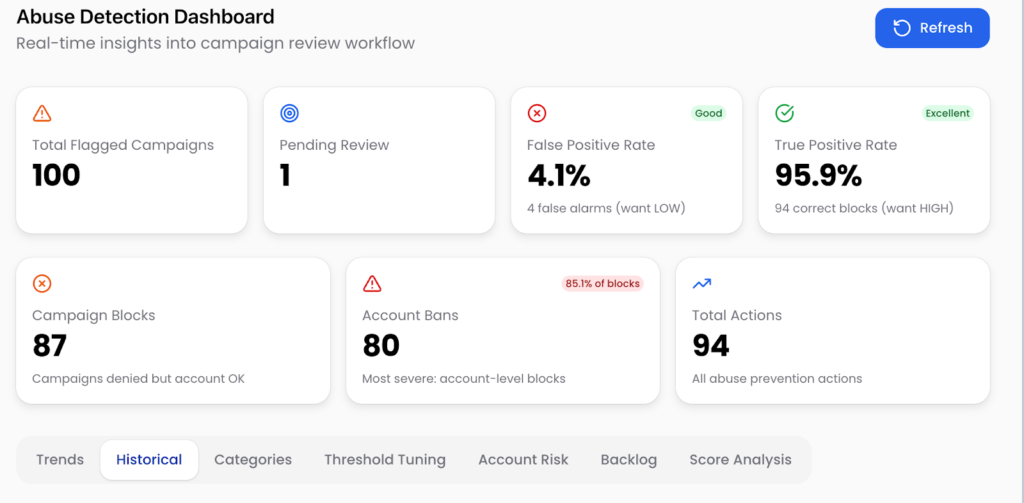

We monitored and kept track of manual reviews using a combination of monday.com Boards and monday.com Vibe. Every result from the Abuse Detection was sent to a board, where a reviewer (usually whoever was on-call at the time) could access the campaign data and make a decision. A very easy, simple way to get a UI and give someone access without needing to build anything from scratch. Additionally, with monday.com Vibe, we built an analytics dashboard embedded in the board to track metrics and features such as classification threshold tuning.

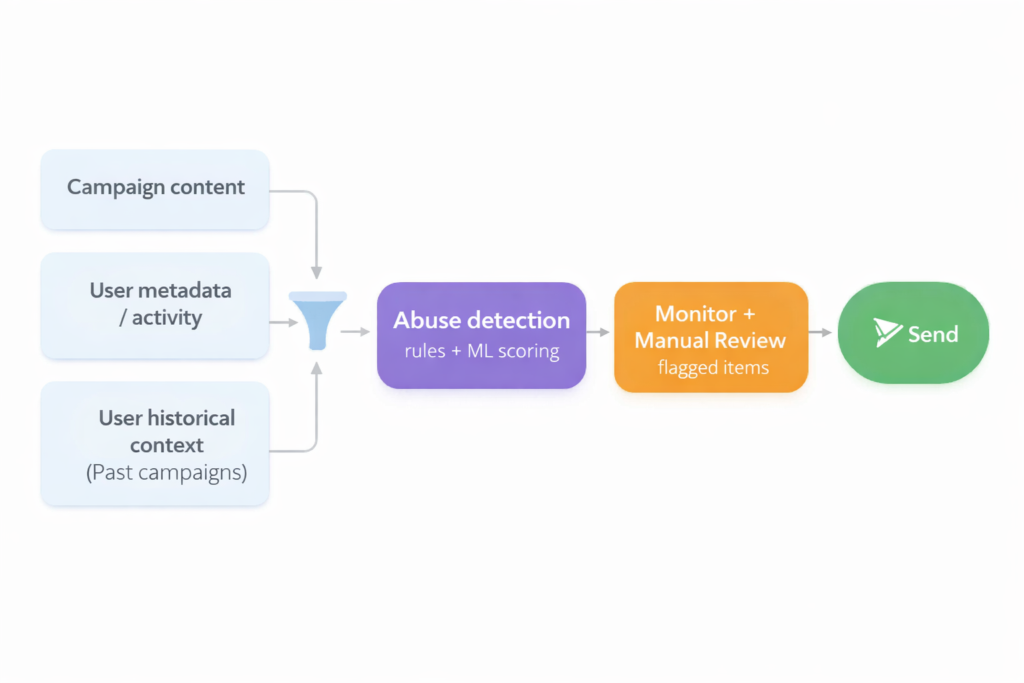

Abuse Detection Flowchart

Abuse Approval Board using Monday Boards and Automations

Abuse Analytics Dashboard using Monday Vibe

With this setup, we prepared for the product launch, and it was a success! Everything worked well, initially. Our True Positive Rate was a stunning 100%, with some false positives, but nothing we couldn’t handle in the manual review process, and nothing that wasn’t supposed to pass through did.

For instance, in October, post-launch at Elevate, monday.com’s annual global conference, the malicious account rate (the number of detected abusive accounts over all new accounts) stood at roughly 6.6%. Our initial content detection layer successfully prevented all abusive campaigns from going through, as we manually double-checked all of them.

Everyone lived happily ever after, and the article ends here – no abusive campaign passed our gate, until…

Whack-a-mole: how feedback loops undermined our defenses

Then we started seeing an abnormal number of new accounts with weird or extremely conspicuous brand names. In November, new account volume increased significantly, and with that, the number of potentially malicious accounts jumped to 16%. This spike also coincided with a massive increase, almost 8x, in flagged campaigns.

We didn’t have an identity verification system in place at the time, which meant that all anyone needed was a valid credit card to access the full power of our product. We also didn’t notice immediately as the numbers were growing. We were, in fact, very happy to see the line go up!

What seemed to have happened was a coordinated effort from a possible group of scammers, and you know that when there’s money to be made, someone is armed with patience and scripting to see if their (scamming) solution has good (illegal) market fit. Of the 184 new accounts we had in November, 29 of them were malicious (created across the month). We did manage to block all of their 85 abusive campaigns except one, which thankfully ended up being sent to no one, as the contact list of that account didn’t have any legitimate user contact yet.

These accounts were testing our system’s defenses, trying to see if and how they could send their phishing campaigns. We noticed the users found a way to “game” our abuse detection system: since we surface to the user immediately whether a campaign is being held for review or blocked, they were able to instantly get a feedback signal on their campaign, and iterate on the body until the scores the classifier was giving were low enough to pass.

Additionally, to add to the noise, there were a bunch of suspicious accounts with content that was hard to judge (most of them are really just bad at making effective marketing campaigns, and they end up looking like spam or suspicious).

We managed to catch these behaviors just in time. At the same time, the content-only abuse detection worked very well in blocking all the poor phishing attempts, their behavior gave us a couple of learning opportunities: some of the account names were just too shady, some of them had famous brand names with typos in them (we lovingly remember in the team Bookling.com, the not-so-well-known shady little sister of Booking.com), but alas, scammers don’t always make these mistakes.

Some of these suspicious accounts were sending innocuous, seemingly legitimate campaigns to see whether they could pass as legitimate users. Others were creating very long, dense campaigns and hiding their JavaScript or encoded phishing links to avoid detection.

The game here was cat and mouse, where the mice were looking for holes in the system to leverage and gather information on them before planning the ultimate cheese theft. The scale of growth of this potential problem gave us an important push – we were defending, but we needed more insurance and risk mitigation.

This highlighted some improvements we had to make in the system:

- Identity verification had to be a strong show-stopper for many of these accounts that use stolen or fraudulent credit cards.

- We needed more signals and information on these accounts, such as how long they’d been customers and whether they had a dedicated account manager. Additionally, we sought other relationships that could cluster account behaviors and help us flag suspicious activity early.

- Our current classifier had been showing weakness with very long inputs, leading the LLM to miss some abusive elements in email bodies.

- We needed to avoid giving too much information back on the platform regarding abuse outcomes to prevent users from leveraging it.

Defending in depth: a hybrid system and future directions

This leads us to the system’s final state. We are currently working on some of the improvements listed above, while some are already live in production. Some of these are:

- A hybrid heuristic and content classification system that embeds additional signals in the content analysis made by the classifier to improve the accuracy of the classification.

- Rate limiting and obfuscation of results for multiple flagged abusive campaigns make it much more time-consuming to try to game the system.

Some other elements we are actively working on include identity and credit card verification, which we strongly believe will block most low-effort abusive users from accessing campaigns, IP pool routing to isolate bad senders and avoiding impacting deliverability for legitimate tenants on the shared IP pool. We’re also focusing on a map-reduce approach to classify longer inputs with LLMs to address the shortcomings of LLMs with longer inputs.

Ultimately, what we discovered through our whack-a-mole game of abuse detection reveals that building an effective defense is less about focusing on building a single perfect model, namely our content-only LLM classification, but architecting a resilient, multi-layered system.

On the one hand, we embed user activity signals alongside semantic content analysis to understand content in context. On the other hand, we evaluate the UX and feedback loops of our system, understanding the ongoing adversarial loop that a malicious user might leverage. It is this approach to defense that enables us to manage the crucial tension between high recall and high precision, protecting both our platform and our users.